The

most common question that curator Edward Bleiberg fields from visitors

to the Brooklyn Museum's Egyptian art galleries is a straightforward but

salient one: Why are the statues' noses broken?

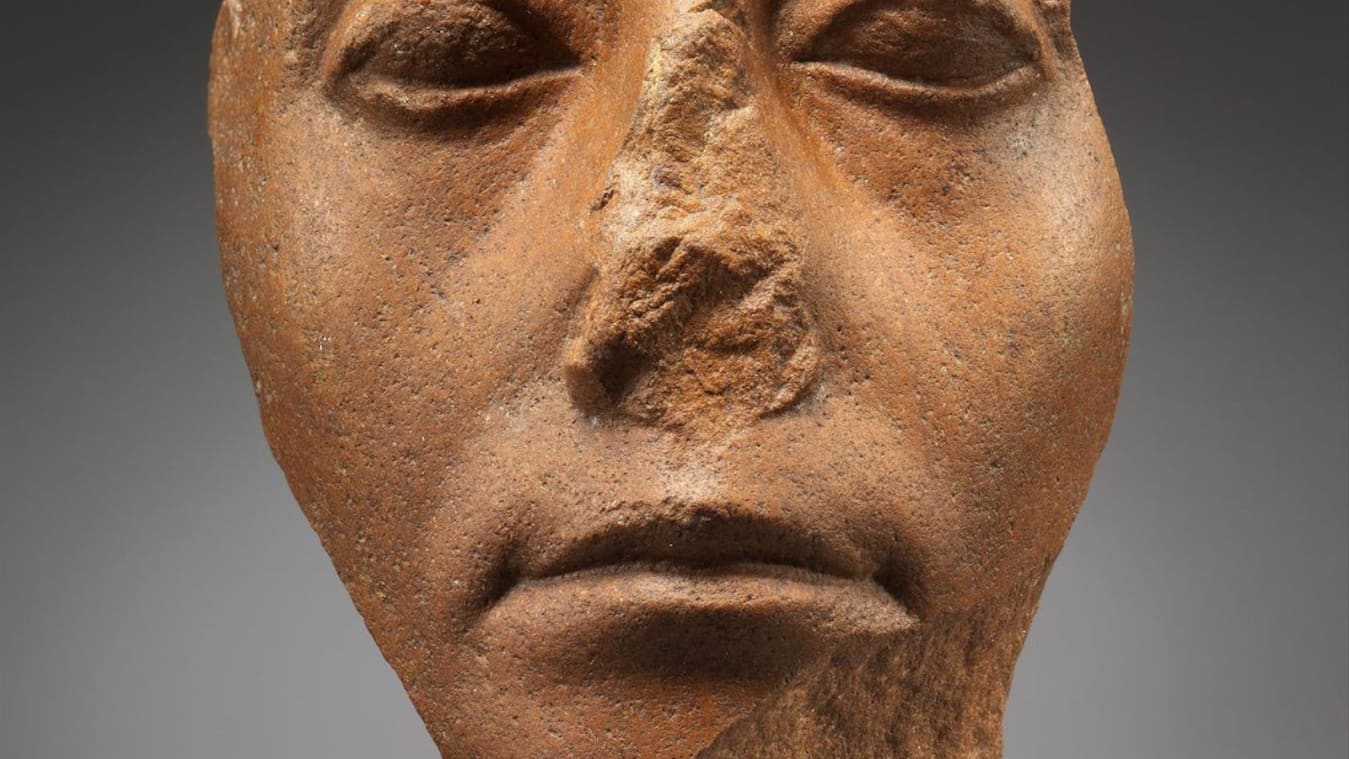

The most common question that curator Edward Bleiberg fields from visitors to the Brooklyn Museum's Egyptian art galleries is a straightforward but salient one: Why are the statues' noses broken?

Bleiberg,

who oversees the museum's extensive holdings of Egyptian, Classical and

ancient Near Eastern art, was surprised the first few times he heard

this question. He had taken for granted that the sculptures were

damaged; his training in Egyptology encouraged visualizing how a statue

would look if it were still intact.

It

might seem inevitable that after thousands of years, an ancient

artifact would show wear and tear. But this simple observation led

Bleiberg to uncover a widespread pattern of deliberate destruction,

which pointed to a complex set of reasons why most works of Egyptian art

came to be defaced in the first place.

Bleiberg's research is now the basis of the poignant exhibition "Striking Power: Iconoclasm in Ancient Egypt."

A selection of objects from the Brooklyn Museum's collection will

travel to the Pulitzer Arts Foundation later this month under the

co-direction of the latter's associate curator, Stephanie Weissberg.

Pairing damaged statues and reliefs dating from the 25th century BC to

the 1st century AD with intact counterparts, the show testifies to

ancient Egyptian artifacts' political and religious functions -- and the

entrenched culture of iconoclasm that led to their mutilation.

In

our own era of reckoning with national monuments and other public

displays of art, "Striking Power" adds a germane dimension to our

understanding of one of the world's oldest and longest-lasting

civilizations, whose visual culture, for the most part, remained

unchanged over millennia. This stylistic continuity reflects -- and

directly contributed to -- the empire's long stretches of stability. But

invasions by outside forces, power struggles between dynastic rulers

and other periods of upheaval left their scars.

"The

consistency of the patterns where damage is found in sculpture suggests

that it's purposeful," Bleiberg said, citing myriad political,

religious, personal and criminal motivations for acts of vandalism.

Discerning the difference between accidental damage and deliberate

vandalism came down to recognizing such patterns. A protruding nose on a

three-dimensional statue is easily broken, he conceded, but the plot

thickens when flat reliefs also sport smashed noses.

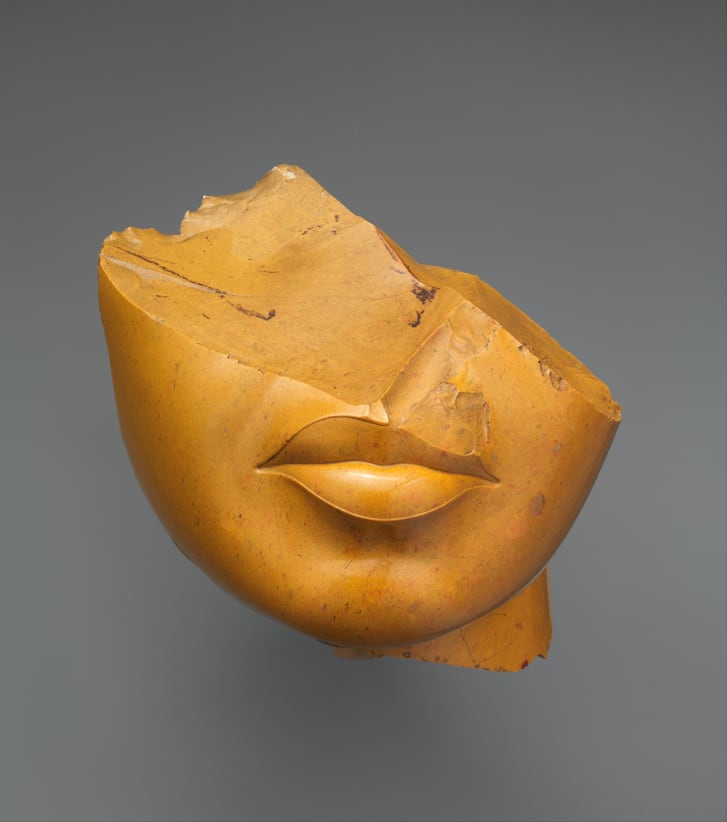

The

ancient Egyptians, it's important to note, ascribed important powers to

images of the human form. They believed that the essence of a deity

could inhabit an image of that deity, or, in the case of mere mortals,

part of that deceased human being's soul could inhabit a statue

inscribed for that particular person. These campaigns of vandalism were

therefore intended to "deactivate an image's strength," as Bleiberg put

it.

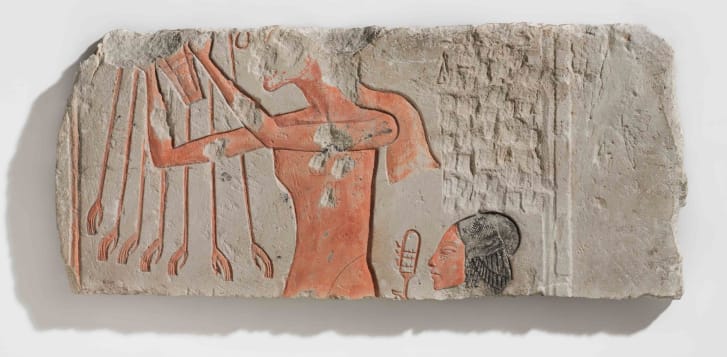

Tombs

and temples were the repositories for most sculptures and reliefs that

had a ritual purpose. "All of them have to do with the economy of

offerings to the supernatural," Bleiberg said. In a tomb, they served to

"feed" the deceased person in the next world with gifts of food from

this one. In temples, representations of gods are shown receiving

offerings from representations of kings, or other elites able to

commission a statue.

"Egyptian

state religion," Bleiberg explained, was seen as "an arrangement where

kings on Earth provide for the deity, and in return, the deity takes

care of Egypt." Statues and reliefs were "a meeting point between the

supernatural and this world," he said, only inhabited, or "revivified,"

when the ritual is performed. And acts of iconoclasm could disrupt that

power.

"The

damaged part of the body is no longer able to do its job," Bleiberg

explained. Without a nose, the statue-spirit ceases to breathe, so that

the vandal is effectively "killing" it. To hammer the ears off a statue

of a god would make it unable to hear a prayer. In statues intended to

show human beings making offerings to gods, the left arm -- most

commonly used to make offerings -- is cut off so the statue's function

can't be performed (the right hand is often found axed in statues

receiving offerings).

"In

the Pharaonic period, there was a clear understanding of what sculpture

was supposed to do," Bleiberg said. Even if a petty tomb robber was

mostly interested in stealing the precious objects, he was also

concerned that the deceased person might take revenge if his rendered

likeness wasn't mutilated.

The

prevalent practice of damaging images of the human form -- and the

anxiety surrounding the desecration -- dates to the beginnings of

Egyptian history. Intentionally damaged mummies from the prehistoric

period, for example, speak to a "very basic cultural belief that

damaging the image damages the person represented," Bleiberg said.

Likewise, how-to hieroglyphics provided instructions for warriors about

to enter battle: Make a wax effigy of the enemy, then destroy it. Series

of texts describe the anxiety of your own image becoming damaged, and

pharaohs regularly issued decrees with terrible punishments for anyone

who would dare threaten their likeness.

Source: CNN

No comments:

Post a Comment